Guide for debriefing elections

Best practices and examples for gathering feedback from poll workers or staff.

What you’ll need

- Sample feedback survey for poll workers (Google Form)

- Sample survey questions (Google Doc / Microsoft Word)

- Additional sample survey questions (Google Doc / Microsoft Word)

- A Google account to access, copy, and edit the sample survey

Getting Started

Debriefing will allow you and your poll workers or staff to create a space to reflect on what went well and what could be improved in the administration of your election. In turn, it will also allow you and your team to understand, analyze, and improve upon your processes. A well-designed post-election survey can help your office improve the way they recruit, train, and retain poll workers.

Debriefing demonstrates that your election department values the work, effort, and commitment of your workers in serving voters.

This guide covers three main steps for your debriefing process:

- Creating a survey to gather information from your workers

- Analyzing their survey responses

- Learning more with a group conversation

In addition, after this internal work, you may choose to take an optional fourth step: sharing your learnings with your staff and, perhaps, with the public.

Using the toolUsing the tool

Creating a feedback survey1. Creating a feedback survey

A survey is a simple way to gather information from your poll workers or full-time staff. By adapting a sample survey that we’ve created, you’ll be able to quickly produce a customized survey to meet your needs.

Getting started with a sample survey

It’s easy to copy this sample survey and begin adapting it.

You’ll need a Google account to access the survey. If you’re logged in to a Google account, click the link below. Then, click the Use Template button.

Access the sample feedback survey for poll workers (Google Form)

Now you’ve got your own copy of the survey. Give your new copy a name, and specify the location on Google Drive where you’d like to store the survey. You can then make edits and disseminate the survey, ensuring that the only person who can see the responses is you.

Sample survey questions

If you’d like to just copy the sample survey’s questions, they’re here, for your reference. Or, you can download the questions in a Microsoft Word document.

Your Role and Experience Level

- When did you work? [Options: During early voting; on Election Day]

- What was your role in this election? [Options: Supervisor; check-in clerk; ballot clerk; voting tech clerk; greeter clerk]

- How many times have you served as a poll worker? [Options: This was my first time; 2-3 elections; 4-5 elections; 6-7 elections; 8+ elections]

Before Election Day

- Reflecting on the training that I received before the election, I felt prepared to serve voters at my polling place. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- Were there any topics in training that you would have liked to spend more time on? [Open-ended question]

- Did you feel like your suggestions and concerns were taken into account in the lead up to this election cycle? Please provide illustrative examples. [Open-ended question]

On Election Day

- Please describe your experience working on Election Day. What stands out? [Open-ended question]

- I understood how to set up the polling place in the morning. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- I understood how to check voters in. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- I understood how to issue a ballot to a voter. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- I understood how to help voters submit their ballots and complete the voting process. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- I understood how to shut down the polling place when the polls closed. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- We had enough supplies to effectively serve our voters. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- I felt safe serving as a poll worker. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- The team at my polling place worked well together. [Rate agreement on a scale of 1-5]

- What additional support or resources would you need in order to have conducted a more successful election? [Open-ended question]

Next steps and recommendations

- How did you find out about this opportunity? [Options: Through a family member or a friend; through a colleague; social media outreach from the election department; the election department’s website; other]

- Would you recommend serving as a poll worker? Why or why not? [Open-ended question]

- Are you interested in working in our office in other roles, before or after future elections? [Options: Yes, please contact me with additional opportunities; no]

- Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience? [Open-ended question]

Choosing a survey tool

The sample survey we’re providing uses Google Forms, a free, web-based survey administration tool. Google Forms will allow you to collect the data in one place and easily see trends in the form of visualized data, such as charts and bar graphs. As an administrator, you can customize the form, make certain questions required and others optional, set the form so it accepts anonymous submissions, and so on.

If you prefer to not use Google Forms, you can consider tools such as Jotform, Typeform, or SurveyMonkey to run the surveys.

Selecting survey questions

The sample survey features both Likert scale questions and open-ended questions. As you adapt the survey for your needs, consider the benefits and drawbacks of these question types.

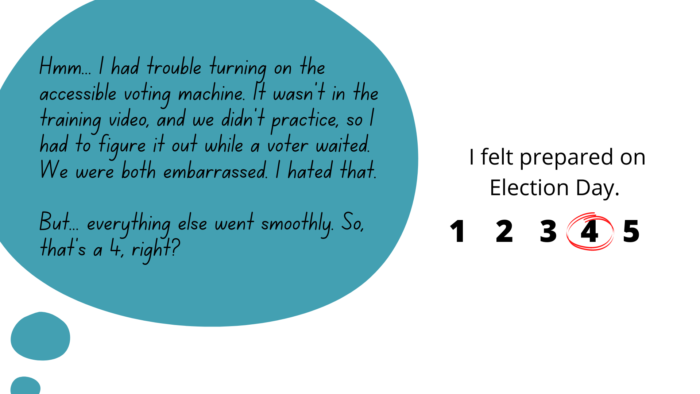

When you ask someone to rate something on a scale of 1-5, you’re using a Likert scale. Survey questions like these are useful because they produce objective, quantitative data (numbers) from people’s subjective experiences.

But while numbers are easy to analyze at a glance, they don’t provide much insight. For instance, if a poll worker rates their training experience as a 2 out of 5, you can see there’s a problem, but that rating alone doesn’t tell you how to address the problem.

The situation is reversed with open-ended questions.

Open-ended questions ask people to respond to a prompt in writing. Because the responses are qualitative, they can be challenging to analyze. For instance, comparing one person’s written response to another person’s will take more time and effort since you’re not just comparing numbers. But the reward with open-ended responses is a greater degree of insight and specificity about the person’s experience.

We’ll share more information about working with open-ended and Likert scale responses later, in the “Analyzing Survey Responses” section. For now, just reflect on whether quantitative or qualitative data would be most helpful for each of the topics that your survey will cover.

To help in the process of customizing your survey and selecting questions, consider checking out the real-world examples of surveys created by election departments in the Resources section below.

Additional ideas for questions to include

These questions are not included in the sample survey linked above, but are ideas for questions to add if they fit with your survey’s goals. You can copy them below or download the questions in a Microsoft Word document.

Before Election Day

- Did you attend in-person training or online?

- What features of the training are the most valuable to you (Powerpoint presentation, manual, job aids, videos, hands-on)?

- How can we improve the training?

- How did you feel about the length of time the training took to complete?

On Election Day

- What were the top three challenges on Election Day for your team?

- Did you have any issues with any of the equipment?

- What was your favorite part about working with the equipment at the polling locations?

- Did you have any difficulty gaining access to your polling place?

- Did you observe or did the voters vocalize any concerns relating to polling place location, layout, parking?

- Did you have adequate wifi connectivity at your polling place?

- Did you have an adequate number of power outlets and extension cords?

- How well did the call center or team lead help you resolve procedural issues?

- How quickly did the Troubleshooter help you resolve equipment issues?

- If you requested additional supplies, did you get them on time?

Next steps and recommendations

- Was there anyone on your team, or yourself, who may be a good fit for an elevated role in the future?

- Anything you would like to share with us that would help us improve our service to you and to the voters of this county

Making your survey anonymous or not

The sample survey doesn’t ask respondents for any identifying information, so it’s anonymous. But if you prefer, you can collect the names of those who are filling out the survey.

The benefit of an anonymous survey is that you may receive more honest feedback, but the benefit of collecting respondents’ names is that you can follow up with specific individuals about their responses. It’s up to you.

Being timely with your survey

While we understand that you will have many competing priorities in the weeks following an election, we suggest that you set the expectation that your survey be filled out within one week of the election in order to capture experiences while they’re still fresh.

Analyzing survey responses2. Analyzing survey responses

Once you have gotten responses to your survey, you’ll need to analyze the data that you’ve collected.

Although it isn’t essential that you do this analysis work before holding the group conversation, you can get more from the conversation if you have an understanding of how your workers responded to the survey. For instance, if you notice a trend among responses but want more information, you can directly ask about that in your group conversation.

Analyzing Likert scale responses

Likert scales transform qualitative, descriptive data into quantitative, numbers data. Numbers are easy to analyze because patterns appear quickly, but Likert scale responses do have some shortcomings that you’ll need to pay attention to.

We already mentioned how one drawback of quantitative data is that numbers can tell you what someone is feeling but not why, but there’s an additional challenge that you need to keep in mind when analyzing Likert scale responses: they tend to produce flattering results.

Unless somebody had a significantly negative experience, they’ll tend to avoid selecting a 1 or 2 out of 5. If their experience could be improved, they’ll probably report 3, 4, or even 5. If they’re worried about being mean — especially if a low score would reflect badly on a specific person — they’ll often report 4 or 5, even if there’s significant room for improvement.

Why do Likert scale responses skew positive? Because they don’t allow respondents to give reasons or explanations. You have no choice but to generalize, to paint with broad strokes. And that often means minimizing problems.

Ultimately, Likert scale survey responses are still highly useful; you just need to remember that everyone’s answers are probably shifted toward the positive side.

So, for example, if 80% of your poll workers report a 5, but the remaining 20% only report a 4, that’s a result that you should pay attention to, even though 4 might seem like a high number and 20% a small proportion. There may still be a problem for you to investigate.

In short, don’t assume that there were no problems just because you don’t see any 1s or 2s among your responses.

Analyzing open-ended responses

Open-ended questions invite people to speak their mind, go into detail, and focus on what they think is important. These questions can produce insightful responses, but the job of analyzing them can be messy.

How do you analyze a bunch of sentences? How do you find patterns when everyone approached the question in a different way? How do you juggle responses from 50 poll workers, or 200 poll workers, or more? There are a few techniques you can use.

The easiest technique is just to read and take notes. That’s it! Read thoughtfully, curiously, and take notes about what you learn. Sometimes it helps to organize your notes into categories, such as 1) compliments, 2) suggestions, 3) questions. Here at CTCL, we often categorize feedback into three simple groupings: 1) things to stop, 2) things to start, and 3) things to continue. It helps us organize feedback into concrete next steps.

A second, more time-consuming technique is tallying, also known as qualitative coding. When you read a response, assign a short label. For instance, if you read a response like “I love working elections, but I’m so exhausted after a 15-hour day!” you could assign a label like “tired” or “workload” to capture the negative feelings. You could add a 2nd label, like “loves elections,” to capture those positive feelings. Then, move onto the next response and assign more labels.

You’ll discover that some labels repeat frequently, and others don’t. You may also start combining labels, or breaking them apart, or editing your wording. That’s fine!

When you finish labeling every response, go through a second time with your revised list of labels. If you make more revisions, repeat the process as many times as you need. When you’re finished, tally the frequency of each label. Now you have numbers, which make patterns much easier to see! You can also disaggregate these tallies (see explanation below) to reveal even more patterns.

A third technique, after you’ve done some initial analysis, is to follow up to investigate further. The reason is that open-ended questions allow so much flexibility that everyone answers in a different way.

For instance, let’s say you survey 100 people about their Election Day experience, and only 10 mention feeling exhausted. Does that mean only 10% felt exhausted? No. Instead, it means only 10% of people chose to mention exhaustion in their reply. You don’t have data for the other 90%. If you want more data, you’ll need to follow up.

Keep in mind that just because a problem wasn’t reported by many people doesn’t mean it’s not worthy of attention. For instance, if only one person mentions a safety hazard, you should still look into it.

But, of course, sometimes it does matter how common an experience was. Did this problem happen at one specific polling place or at every polling place? If one of your 200 voting machines has a frayed power cord, is it possible that the other 199 might be vulnerable to the same problem?

Don’t be afraid to put on your detective hat and ask more questions. Just remember to focus, only seeking follow-up information that will actually help you make decisions.

Disaggregating data

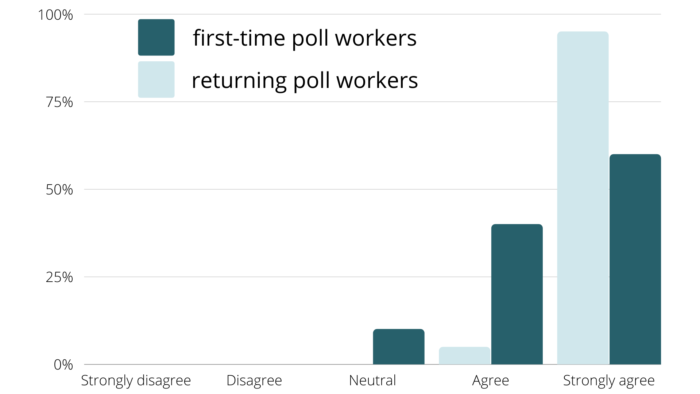

Finally, an important analysis technique that can help you find patterns is to disaggregate your data. Disaggregation means separating responses from different groups of people.

The reason is clear: different people have different experiences, and if you only look at the overall (aggregated) responses, you’ll miss how experiences may vary for different people.

For example, let’s say 90% of your poll workers overall report that they “strongly agree” that they were prepared for Election Day. If you disaggregate the responses into two groups — returning poll workers and first-time poll workers — you may find that something like 95% of returning poll workers strongly agreed they felt prepared, whereas only 60% of first-time poll workers strongly agreed.

Disaggregating the data has shown that the experience is very different for the two groups. So, your next step might be to consider what additional training or support might help first-time poll workers.

Considering your sample size

When analyzing your data, you might wonder whether or not you have enough responses. For instance, if you sent a survey to 50 of your workers and only 20 people completed it, you may wonder if that’s a large enough sample size to provide trustworthy or representative information about the group as a whole. It can be tempting to dismiss responses from a group that seems small.

But in general, unless you’re trying to get published in an academic journal or use your data to make predictions, statistical significance and sample size should not matter for your debrief and process-improvement work.

Assume that everybody you survey is significant. For instance, imagine you have 40 returning poll workers and only 3 first-time poll workers. If all 3 first-time poll workers report that they didn’t feel prepared, that’s a real, meaningful pattern. You shouldn’t dismiss their answers just because they’re a small group.

Learning more with a group conversation3. Learning more with a group conversation

Now that you’ve sent the survey and analyzed the responses, you can dig deeper by holding a group conversation with your poll workers or election staff.

The group conversation is helpful for a few reasons.

First, although your survey has given you individual responses, elections are run by groups of people, so it can be helpful to promote discussion and produce feedback in a group setting. Second, the conversation gives you the opportunity to gather more information about trends that you noticed in survey responses. So, for instance, if you noticed complaints about the helpfulness of training, you can prepare questions to better understand how training could be improved. And finally, you can bring your ideas for how to address challenges to the conversation and get feedback on them in real time.

To make it easier for you, we’ve prepared sample discussion questions that you can adopt and customize for your needs. Just like the sample survey, these questions are organized to first ask about people’s experiences before and on Election Day and then seek feedback regarding next steps and recommendations.

The sample questions focus on the experiences of poll workers, but you can adapt them for use with full-time election staff if needed.

Sample discussion questions

Before Election Day

- What were the expectations for this election to run correctly?

- How were those expectations met? How were those expectations not met?

On Election Day

- What do you feel proud of when you think about the process of serving voters at the polling place?

- What do you feel could be improved?

- How well did your team work together on Election Day? How could people work better together next time?

Next steps and recommendations

- What other recommendations would you make for the next election?

- Would you recommend serving as a poll worker? Why or why not?

Group conversation logistics

We recommend for you to schedule the group conversation so that it takes place within three weeks of the election. This will help make sure that the information you capture is timely and accurate.

In terms of length, we suggest allotting 45-60 minutes for your group conversation.

Since poll workers may not have the opportunity to be paid for participating in the conversation, consider how to incentivize them to attend the session. Is there something you could provide them to motivate their attendance and show your appreciation?

Sharing your findings4. Sharing your findings

At this point, you’ve sent the survey, you’ve analyzed the responses, and you’ve held a conversation to dig deeper. Hopefully you learned some thing in your debrief process and are making plans for incorporating your findings and making improvements. Congratulations!

You’re done, right? Well, not so fast. People invested time and thoughtfulness into your survey. They turned their experiences into data and willingly handed it to you. They’re trusting you to listen, understand, and take their ideas seriously. The most respectful thing to do is share back what you learned.

Consider how you might share the information you’ve gathered and with whom. Does it make sense to share your findings internally, with the public, or to do both?

When sharing internally, emphasize what you learned, why it’s important, and what you’re planning to do to address the feedback. What trends are important to share with leadership or your staff? What’s the best venue, or format, for sharing the information?

When sharing with the public, consider what information will be most useful to a general audience, remembering that it’s okay to hold back details that may be sensitive. What findings or upcoming changes will be most interesting to the public? How can you strike a balance between openness and discretion?

Ultimately, now that you’re familiar with election debriefs, you can take some time to reflect on how to incorporate the role of debriefing into your operations moving forward. We suggest spending some time thinking through how you may want to incorporate the feedback that you receive from your debriefs in your planning for future elections and also thinking through the timing of when and how frequently you would like to conduct debriefs in the future.

Resources5. Resources

Sample survey for you to customize and use

- Sample feedback survey for poll workers (Google Form)

- Sample survey questions (Google Doc / Microsoft Word)

- Additional sample survey questions (Google Doc / Microsoft Word)

Examples of election surveys from the field

- Nevada County, California: Vote center worker post-election survey

- El Paso County, Texas: Election worker survey

- Ramsey County, Minnesota: Election judge survey

- Ramsey County, Minnesota: Student election judge survey

Guidance for survey design

- Caroline Jarrett: “Surveys That Work: A Practical Guide for Designing Better Surveys”

Customizing for your office

Any tips for customizing this resource for my office?

The sample survey includes questions for poll workers, and it makes guesses about the kinds of activities that typical poll workers do. If your poll workers have different responsibilities than those covered by the questions, simply customize the questions as needed.

You can also add, remove, or edit questions to focus on different goals for your office. For instance, post-election surveys can be a good place to ask about new procedures or equipment you are using, or to check in about how Standards of Conduct are maintained.

Be careful about adding too many questions, though. Although there’s a lot of great information you can gather by adding questions, you can also overdo it. You may get a lower response rate if completing the survey takes a long time. Try to focus on the most important questions and remove questions that aren’t as valuable to you.

You can also adapt the survey for full-time election staff or other temporary workers. You just need to update some of the questions to more appropriately focus on their roles.

How do I know if this resource is helping?

There are a few different goals this resource can help you achieve. The information gathered from your poll workers’ responses can give you ideas on how to improve processes for your next election. If you make changes that smooth out concerns raised by your poll workers, that’s a big win for your debriefing process.

You can also see higher retention rates in poll workers, or your poll workers might report that they feel their voices have been heard. And, you can put together data that can help you tell the story of how the election went to your office, other government leaders, or the public.

Which Values for Election Excellence does this resource support? Why?

Values for the U.S. Alliance for Election Excellence define our shared vision for the way election departments across the country can aspire to excellence. These values help us navigate the challenges of delivering successful elections and maintaining our healthy democracy.

Alliance values are designed by local election officials, designers, technologists and other experts to support local election departments.

You may find this tool especially helpful for these Values:

- Continuous improvement. Obtaining feedback from poll workers and your team is invaluable for refining procedures for future elections.

Sharing Feedback

How was this resource developed?

This resource combines some questions that have been put into practice by jurisdictions with new questions based on research and expert guidance. Share your experience with this resource and improve it for your peers by reaching out via support@ElectionExcellence.org

How do I stay in touch?

- For the latest news, resources, and more, sign up for our email list.

- Have a specific idea, piece of feedback, or question? Send an email to support@ElectionExcellence.org