Checklist for Combating Election Misinformation

A framework to help election departments respond to influence operations

What you’ll need

- Download the combating election misinformation checklist (.docx file, 780KB)

- Standard communications platforms like a website and social media accounts for your election department

Getting started

Begin by downloading the checklist (found above).

Once you have the checklist, you can review the recommended steps and begin implementing them. For details on each step, refer to the best practices in the “Using the Tool” section below.

Don’t feel like you need to tackle the whole checklist at once though: you can choose which items are within your office’s current reach and start prioritizing from there. There’s plenty of value in small, incremental improvements.

Using the toolUsing the tool

Getting ahead of influence operationsGetting ahead of influence operations

To reduce the impact of misinformation, preparation is key. These are all things you can do in advance to make influence operations less disruptive:

- Be vocal about the problem and drive people to trusted sources

- Show your election office as an official source of information

- Publish accurate and useful information regularly

- Create a rapid response program or telephone line

- Secure your communication channels

- Build relationships with social media and your website publisher

- Learn how to report false content on social media

- Establish media monitoring to spot mentions or false info

- Strengthen relationships with local media and journalists

- Work with fact checking organizations

- Prepare your communications plan and procedures

Be vocal about the problem and drive people to trusted sources

First, simply talk about the problem of misleading election information. This might look like a page on your website about the issue or a series of tweets that debunk common voting myths.

Or, the next time you’re interviewed for a news story, mention that one of your top concerns is people being misled about how to participate in elections.

No matter how you address the issue, always mention a source or two of trustworthy information for voters to rely on – for instance, your election website and the Secretary of State’s X (Twitter) account.

You can see that basic approach in this nice campaign from the California Secretary of State in 2018. The message is simple, and it drives people to the SOS website.

Show your election office as an official source of informationShow your election office as an official source of information

Next, make sure that your election department is immediately recognizable as an official source of information. That means doing things like these:

- Set up https and .gov for your election website

- Get verified on social media platforms like Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), and TikTok, if your office uses those platforms.

- Make your social media accounts look and feel official (add a county seal, add info about the upcoming election, show photos of your staff, etc.)

- Have contact information displayed prominently on your website and social media profiles

Need help getting started? Here are some relevant resources.

Getting verified on social media platforms (Facebook, X/Twitter, TikTok)

If your office decides to communicate via social media, it’s important to set up official accounts for your elections department, board, or office itself, rather than using individual accounts that belong to particular staff members or the lead official. There are two big advantages to this approach:

- An official account can maintain continuity through changes in staff and leadership.

- An official account has access to much better verification methods on social media platforms.

Getting verified on each social media platform has a unique process, but regardless of the platform, you should start by making the account appear official even without a verification badge. Here are some steps you can take:

- Match the name of the account to the name of your office, rather than using an individual’s name. Instead of naming the account “Jane Smith, Example County Recorder”, try “Example County Recorder’s Office.”

- Make the profile image your office’s seal or logo. Or, if your office doesn’t have one, use your jurisdiction’s seal.

- Include links to your account to your office’s website and email address in your account’s profile. If you have the ability, it’s also worthwhile to link back to your social media accounts from your official website as well, so visitors can check that your accounts really are connected to your office.

Next, make sure to secure your account. Set up two factor authentication (2FA) where possible. Keep log-in information in a secure place that is accessible to multiple members of your staff, in case the primary person managing the account in your office is unavailable unexpectedly.

Each social media platform has a different process and minimum requirements for getting your account verified. These requirements may change over time, but this guide will give a quick rundown of each that is current to May 2024.

Publish accurate and useful information regularly

In addition to showing you’re a trusted source of information with your dot gov, your county seal, and so on, you need to have a history of publishing useful, accurate information on a regular basis.

Imagine for a moment two county election departments. One county has a strong website full of information, and they post regularly on X (Twitter) and Facebook accounts that are followed by local journalists. The other county’s election website is pretty barebones – basically just election results and some downloadable forms – and they don’t have a social media presence.

If misleading election information is circulating, you can guess which of these election offices will be better positioned to respond and be trusted by their community.

If you’ve got this covered, great. If your website or social media properties need some work, put the time in to schedule regular posts. For ideas and templates, check out:

- VoterCast

- The EAC’s social media toolkit

- The Alliance’s Voter outreach graphics

- CTCL’s training about social media

Create a rapid response program or telephone line

Make sure that if voters have a problem on Election Day, they can get a solution from you instead of venting about it publicly and possibly misleading people. This might be as simple as making sure you have the phone lines sufficiently staffed, or you might decide to create something more advanced.

The Electronic Privacy Information Center says that “Whether [election misinformation is] by design or accident, the best defense is to be prepared with accurate information on election participation and the means to deliver it to those who need it.”

So, it’s a great idea to make sure you have procedure experts on call for voters and journalists who may have questions. And, of course, you’ll need to train them.

Secure your communication channelsSecure your communication channels

Your communication channels are precious. To help avoid any unauthorized user editing your website or commandeering your social media accounts, review who has access and update credentials – especially if you’ve had staff transitions.

Here are some steps to take:

- Review permissions for website and social media

- Improve passwords or use a password manager

- Set up two-factor authentication

- Draft or revise a social media policy

If you need best practices for passwords and two-factor authentication, you can enroll in CTCL’s self-paced cybersecurity courses.

Build relationships with social media and your website publisherBuild relationships with social media and your website publisher

Protecting access to your channels is important, but you should also have contacts prepared in case something bad happens. For a website, this might include your webmaster and your website vendor. For social media, there are also people you can contact for help.

For social media contacts in particular, it is best to use your government email address to make contact, and preferably the one attached to your office’s account. This will help their staff identify that the request or report is coming from a legitimate source.

For your reference, we’re providing contacts for Facebook, X/Twitter, and TikTok. This information is accurate as of May 2024.

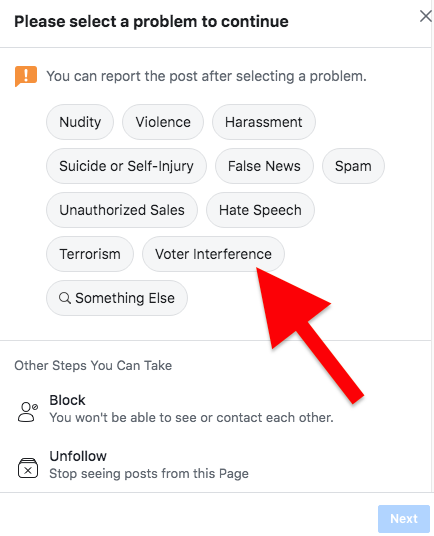

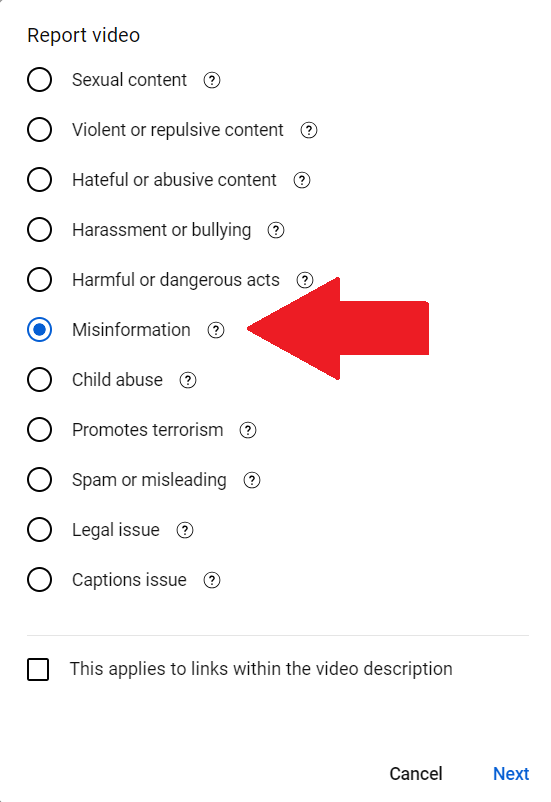

Learn how to report false content on social media

In the event of an influence operation, you should reach out to these contacts, but you should also report the content using the platform’s reporting mechanisms. Below are the steps to report content on the major platforms.

Establish media monitoring to spot mentions or false info

It’s important to know what’s being said about your election department and voting in your area, and media monitoring can help.

Some election authorities have special systems and programs in place to monitor the conversation about elections in their areas, but you can also do simple things like these:

- Set up Google Alerts for your election department’s name

- Regularly check social media notifications and mentions

- Do regular Google searches to spot possible spoof sites

Monitoring is a good habit all the time, but it’s extra important on Election Day.

Strengthen relationships with local media and journalistsStrengthen relationships with local media and journalists

Having good relationships with local journalists can really pay off in the event of an influence operation. If you don’t have strong relationships with reporters, you can build some now.

Ahead of an election, schedule a call with your local media outlets to share information about what voters can expect. This is useful for voters and also establishes a bond with the journalist. Just seeing that you’re proactive will make a positive impression on the reporter and the people who read their story.

In the event of a viral election myth circulating in your area, it’ll be great to have a history with a journalist if you need to go on the record to correct misinformation. Take a look at our Communicating Trusted Election Information series of webinars, specifically the “Working with the media” course, to get some help with building those relationships.

Work with fact checking organizationsWork with fact checking organizations

In addition to local media, national fact-checking organizations can help you deal with election myths.

Here are some ways you can leverage the services of fact checking organizations:

- Tag them in social media posts with false content

- Report false content to them

- Review their resources to verify or debunk questionable information

One caveat to keep in mind is that fact checking takes time; it’s not unusual for fact-check articles to be published several days after the original event.

Prepare your communications plans and procedures

Many election departments have procedures for doing things like issuing press releases and conducting interviews in the event of a crisis. Getting familiar with these plans – or creating them from scratch, if needed – will be helpful so that you don’t need to scramble in a moment of crisis.

If your existing plans don’t cover how to deal with false information, you may want to add that.

For instance, consider how you’ll judge if a myth is significant enough to address publicly. A one-off tweet that’s not getting much attention might be something you just keep an eye on. If an event is more significant, think about how you’ll report the post, contact the media, post a correction, and so on. With all of these steps come questions about who should do the talking, what they should say, and who needs to approve it.

Comms procedures will be different for every election department, but the point is to plan ahead of time to help avoid having to make difficult calls in the heat of the moment. You can get some strategies and tools in the Crisis Communications Toolkit from The Elections Group.

Responding to influence operations

The previous section covers things you can do in advance of an influence event. But what should you actually say or do once an event has occurred and you decide it needs to be addressed?

There’s a huge body of research devoted to effective methods for debunking falsehoods. We’ve digested best practices down into a four-step response framework to make it easy for you.

Customizing for your office

Any tips for customizing this resource for my office?

Depending on your office’s needs and resources, you can pick and choose the different tips from this checklist. You might also approach this by considering what gaps your current strategy has that this can help you address.

You should consider where misinformation about your operations is most likely to appear and where you can best reach the members of your community who may have heard it. But also consider what you are able to maintain effectively – if you don’t have enough staff time to dedicate to a website, several social media platforms, communicating with local media, and so on, it’s usually better to focus on consistency and quality on fewer platforms than to spread your information between more platforms than you can manage.

How do I know if this resource is helping?

There are a few ways to measure the impact of your efforts:

- Get feedback about your efforts and the general information environment from stakeholders in your community, like leaders in your County or Municipal governments, heads of local chapters of political parties, community organizers, and voters.

- Look at engagement metrics on your communication channels. Has traffic to your website increased? Do you have more followers on your social media accounts?

- Monitor trends in misinformation in your community. When you see misinformation posted somewhere, are others citing your office as a trustworthy source of information to respond to it?

Which Standards of Excellence does this resource support?

- Language access

- Voter communications

- Community relationships

- Media relationships

Which Values of Excellence does this resource support? Why?

Values for the U.S. Alliance for Election Excellence define our shared vision for the way election departments across the country can aspire to excellence. These values help us navigate the challenges of delivering successful elections and maintaining our healthy democracy.

Alliance values are nonpartisan and designed by local election officials, designers, technologists and other experts to support local election departments.

You may find this tool especially helpful for this Value:

- Voter-centricity. This resource helps you ensure your voters have access to trusted, accurate information in the many places that they might seek out information about elections.

- Comprehensive preparedness. Misinformation poses challenges to your operations at many levels. This resource helps you prepare to meet those challenges and respond to them effectively when they arise.

To learn more about the Values for Election Excellence, and to see the full list, visit the Alliance website.

Sharing feedbackSharing Feedback

How was this resource developed?

This resource has been put into practice by at least one jurisdiction. Share your experience with this resource and improve it for your peers by reaching out via support@ElectionExcellence.org.

How do I stay in touch?

- For the latest news, resources, and more, sign up for our email list.

- Have a specific idea, piece of feedback, or question? Send an email to support@ElectionExcellence.org